Michelangelo learned to speak in clear, direct monosyllables between chisel strikes at the quarry. His mother was too ill to take care of him, so a stonecutter’s wife became his wet nurse. The hammer and chisels entered his infant body along with the marble dust in his mother’s milk.

His letters reveal details of his relationship with his father, who pressured him to restore the lost family fortune. The hierarchy of Florentine reds, crowned at the top with crimson and scarlet made from the crushed bodies of insects, ended with a pinkish-purple red shade known as oricello made from horse urine and grass. His mother’s family produced it. But that was a long time ago and his father was convinced god had a plan for this son to bring back the full family glory.

Even Michelangelo’s name spoke of this divine hope. Instead of a family name, he was named for the archangel Michael. When his mother was pregnant with Michelangelo she was dragged by a runaway horse. She and Michelangelo survived.

This pressure led Michelangelo to develop his skills dealing with nobles like Vittoria Colonna, a woman to whom he wrote many letters. She responded, referring to the artist as her most singular friend. Once, when she was too ill to correspond at the frequency demanded by his passion for her, she asked him to write less frequently. He was so distraught by the request that he stopped working.

As a woman, she learned to communicate in a hazy way, veiling the meaning of her words and intent. Later, when her poetry was under intense scrutiny by the Inquisitor’s office, they struggled to determine whether or not she was actually heretical in her verse.

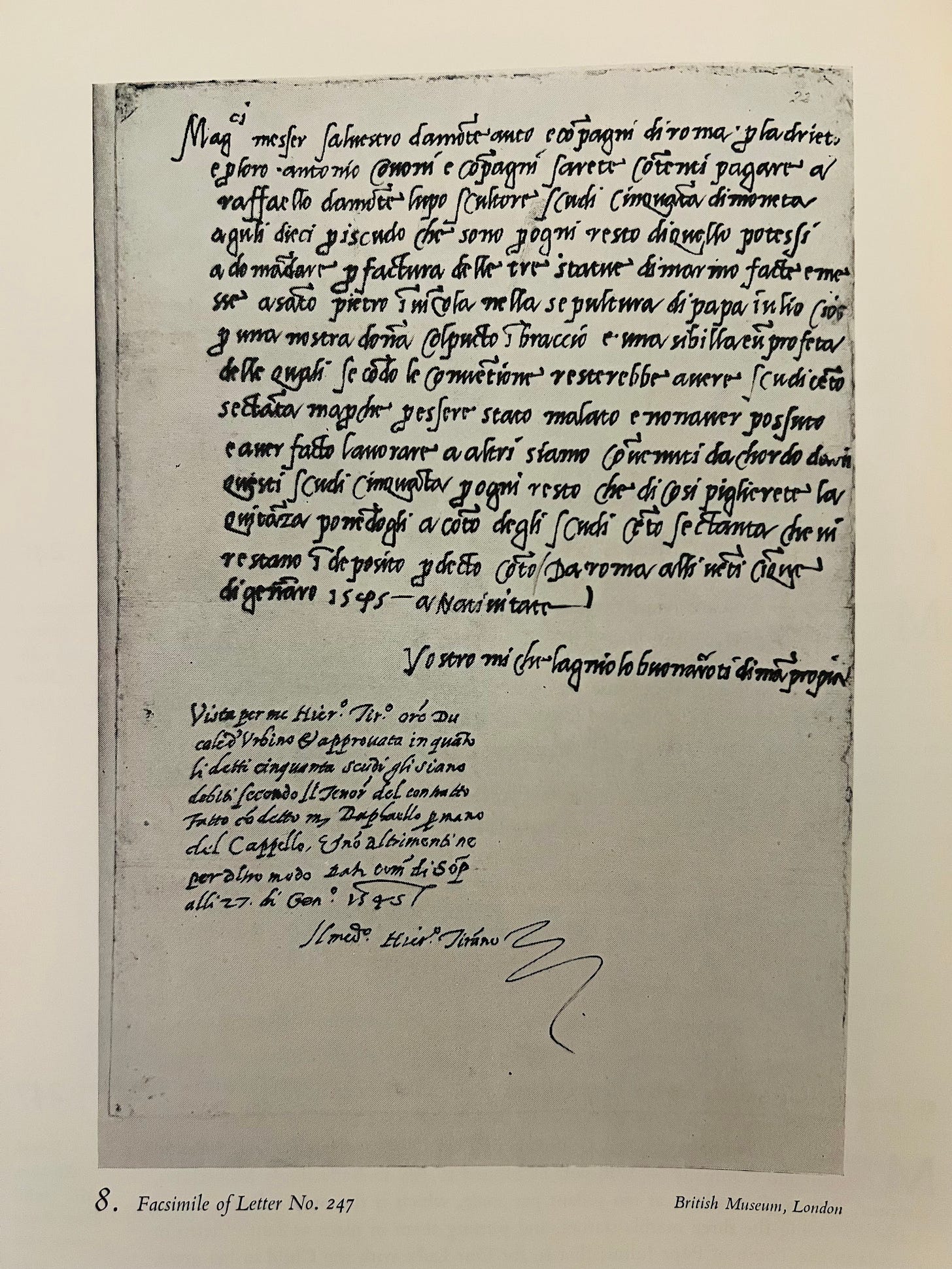

This two volume set of Michelangelo’s letters is an expedition into the heart and soul of an artist who struggled with his fear of death every moment of every day except when he was in Vittoria’s company. She alone could carve him as he carved blocks.